How do you feel about money? I am guessing that you quite like it! In the West, it could be argued that we are obsessed with money. I wanted to delve a little further into the psychology of our relationship with money and this obsession, so did some research on the Creative Commons. I uncovered some interesting ideas and articles. What is the nature of our psychological relationship with money?

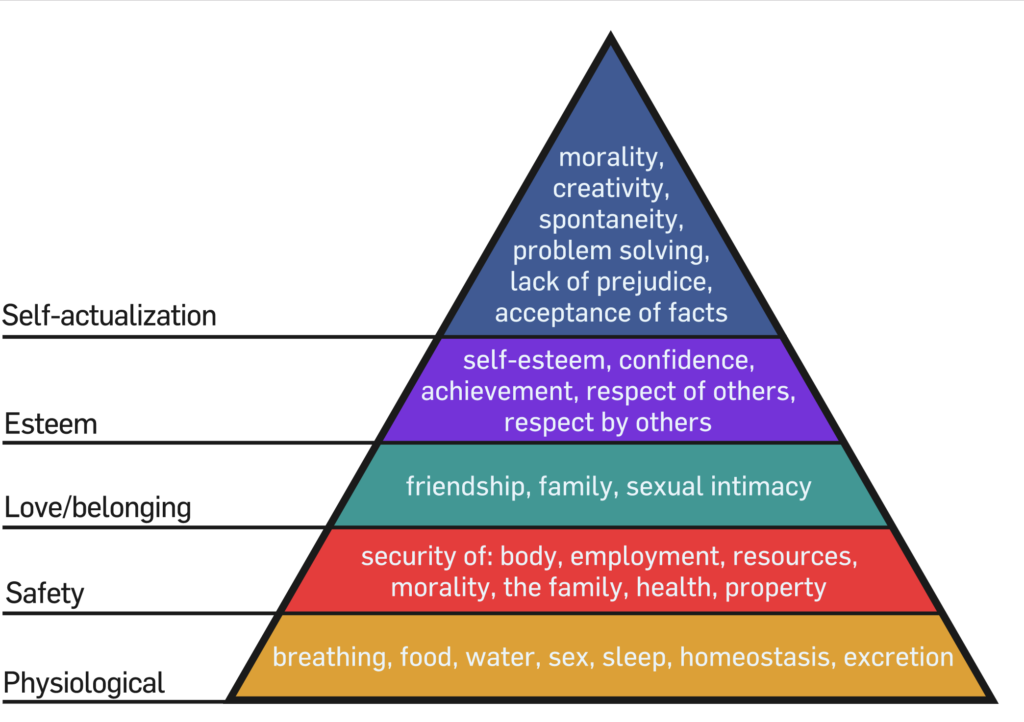

The first point I would like to make is that it is actually quite understandable that some people are motivated by money, from at least one psychological standpoint. When we consider Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the model suggests that we aim to meet our needs progressively. From our most basic, primary needs such as food, water, sex, warmth, toileting, and sleep, through security, employment, and safety needs, love and belonging needs, esteem needs to self-actualisation needs, Maslow proposes that we are not able to start trying to get higher level needs to be met until the lower levels of needs are satisfied.

The article that stimulated this line of thinking in relation to money, provides a very good overview of the different levels of needs. The following excerpt comes from Lumen Learning’s article on Theories of Motivation.

Physiological Needs

The most basic of Maslow’s needs are physiological needs, such as the need for air, food, and water. When you are very hungry, for example, all your behaviour may be motivated by the need to find food. Once you eat, the search for food ceases, and the need for food no longer motivates you.

Safety Needs

Once physiological needs are satisfied, people tend to become concerned about safety needs. Are they safe from danger, pain, or an uncertain future? At this stage, they will be motivated to direct their behaviour toward obtaining shelter and protection in order to satisfy this need.

Love/Belonging Needs

Once safety needs have been met, social needs for love/belonging become important. This can include the need to bond with other human beings, the need to be loved, and the need to form lasting attachments. Having no attachments can negatively affect health and well-being; as a result, people are motivated to find friends and romantic partners.

Esteem Needs

Once love and belonging needs have been satisfied, esteem needs become more salient. Esteem needs refer to the desire to be respected by one’s peers, to feel important, and to be appreciated. People will often look for ways to achieve a sense of mastery, and they may seek validation and praise from others in order to fulfil these needs.

Self-Actualization

At the highest level of the hierarchy, attention shifts to the need for self-actualization, which is a need that essentially equates to achieving one’s full potential. This can be seen in acquiring new skills, taking on new challenges, and behaving in a way that will help you to achieve your life goals. According to Maslow and other humanistic theorists, self-actualization reflects the humanistic emphasis on positive aspects of human nature. Maslow suggested that this is an ongoing, life-long process and that only a small percentage of people actually achieve a self-actualized state.

Explanation of our drive to make money

Can you see what is happening here? Our second level of needs is one of security, property, and employment. So, if we have not taken care of these needs, we will feel a persistent need to earn money to satisfy these needs. Also, as these things are not usually achieved finitely in our lives, we have to work to maintain property and security by continuing to pay our mortgages or rent.

There is another way that our psychological relationship with money is related to our hierarchy of needs as identified by Maslow. It may be that we need money to satisfy our physiological needs, such as food, and so indirectly, money satisfies a primary need. Lumen Learning explains it as follows:

Drives and Homeostasis

An early theory of motivation proposed that the maintenance of homeostasis is particularly important in directing behaviour. Homeostasis is the tendency to maintain a balance, or optimal level, within a biological system. In a body system, a control centre (which is often part of the brain) receives input from receptors (which are often complexes of neurons ). The control centre directs effectors (which may be other neurons) to correct any imbalance in the body detected by the control centre.

The purpose of biological drives is to correct disturbances of homeostasis. Unsatisfied drives are detected by neurons concentrated in the hypothalamus in the brain. These neurons then produce an integrated response to bring the drive back to its optimal level. For instance, when you are dehydrated, freezing cold, or exhausted, the appropriate biological responses are activated automatically (e.g., body fat reserves are mobilized, urine production is inhibited, you shiver, blood is shunted away from the body surface, etc.). While your body automatically responds to these survival drives, you also become motivated to correct these disturbances by eating, drinking water, resting, or actively seeking or generating warmth by moving. In essence, you are motivated to engage in whatever behaviour is necessary to fulfil an unsatisfied drive. One way that the body elicits this behavioural motivation is by increasing physiological arousal.

Drive-Reduction Theory

Drive-reduction theory was first developed by Clark Hull in 1943. According to this theory, deviations from homeostasis create physiological needs. These needs result in psychological drive states that direct behaviour to meet the need and, ultimately, bring the system back to homeostasis. When a physiological need is not satisfied, a negative state of tension is created; when the need is satisfied, the drive to satisfy that need is reduced and the organism returns to homeostasis. In this way, a drive can be thought of as an instinctual need that has the power to motivate behaviour.

For example, if it’s been a while since you ate, your blood sugar levels will drop below normal. Low blood sugar induces a physiological need and a corresponding drive state (i.e., hunger) that will direct you to seek out and consume food. Eating will eliminate hunger, and, ultimately, your blood sugar levels will return to normal.

Drive-reduction theory also emphasizes the role that habits play in the type of behavioural response in which we engage. A habit is a pattern of behaviour in which we regularly engage; once we have engaged in a behaviour that successfully reduces a drive, we are more likely to engage in that behaviour whenever faced with that drive in the future (Graham & Weiner, 1996).

Primary and Secondary Drives

Drive-reduction theory distinguishes between primary and secondary drives. Primary drives are innate biological needs (e.g., thirst, hunger, and desire for sex) that are usually necessary for survival. Secondary drives, on the other hand, are not usually necessary for survival and are often linked to social or identity factors (e.g., the desire for wealth). Secondary drives are associated with primary drives because the satisfaction of secondary drives indirectly satisfies primary drives. For example, the desire for wealth is not necessary for survival; however, wealth provides you with money that can be used to acquire food, shelter, and other basic needs, thereby indirectly satisfying these primary drives. Secondary drives become associated with primary drives through classical conditioning.

Money is only motivating to a point

There is further research that suggests that while money is motivating in some cases, it becomes a lot LESS motivating when we have enough of it. In fact, above a certain wage, a moderate increase in money only corresponds to a very small increase in happiness. Money is motivating to people in low-paying jobs, but once we have more than say USD $40,000 a year, we become more motivated by other things such as expertise, autonomy, and purpose (Pink, 2010).

Money as a form of reciprocal altruism

But this is where it gets really interesting because although we use money to achieve and get our own needs met, the success of money as a system of organisation in our society is based on the fact that it is a form of reciprocal altruism.

Say what?! I know! It is a very interesting and exciting idea. The idea is that if you need anything, you can give someone money for the valuable thing they have. The person who gives you what you need is doing you a big favour. Likewise, when you earn money of your own, you get money for providing value to people. You are then able to use that value to get your needs met from others, in a sophisticated form of reciprocal altruism. I found this idea in a very interesting article written by Daniel Krawisz of the Satoshi Nakamoto Institute. The article is called Reciprocal Altruism in the Theory of Money and is a fascinating read. It explains this theory more fully through game theory, genetics, and economic theory.

This theory explains why the system of money is so widespread in society and why it would be very difficult to overthrow this system. It puts another spin on our psychological relationship with money. I like it a lot though because it provides an explanation of how despite what it feels like on the ground, with people swindling and hustling us, money is actually a form of being good to each other. And perhaps that is why it holds society together, even though it feels evil sometimes. Maybe because some of the players defect, or do not act altruistically as in the Prisoner’s Dilemma as explained by Krawisz.

References:

Lumen Learning, Theories of Motivation <https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-psychology/chapter/theories-of-motivation/> Accessed 29th August 2019.

Daniel Krawisz, 2014, Reciprocal Altruism in the Theory of Money. <https://nakamotoinstitute.org/reciprocal-altruism-in-the-theory-of-money/ > Satoshi Nakamoto Institute. Accessed 29th August 2019

Dan Pink (2010) “The surprising truth about what motivates us” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6XAPnuFjJc&feature=related

Benjamin Todd, 2017, “We reviewed over 60 studies about what makes for a dream job. Here’s what we found.” https://80000hours.org/career-guide/job-satisfaction/

This article is licenced under a Creative Commons – Attribution and Share-Alike Licence. You may use the content and adapt it to your needs, as long as you provide attribution in the form of a link to this article and republish with the same Creative Common licence terms.

Leave A Comment